May Is Asian American Pacific Islander Month

May 22, 2019

What does it mean to be Asian? It’s a question that Asians immigrants in America have been asking themselves since the dawn of immigration. People from all over Earth’s largest continent have been pouring into the U.S. lately and are the fastest growing immigrant group in the country, seeking a better life for themselves and their children. They face the challenge of balancing their homeland’s culture with the individualistic, fast pace of American life, along with discrimination from neighbors, bosses, and immigration officials for coming from a different culture, language, and race.

Meanwhile, Pacific Islanders and Native Hawaiians have always been here. Their ancestors were voyagers of the Pacific who built incredibly complex civilizations all over the ocean’s many islands, including Hawaii. Sadly, European and American imperialism robbed them of their land and now exploits their beautiful islands and cultures for vacations (think fake leis and luaus). To find work and seek opportunities, Pacific Islanders have had to leave their homelands for the mainland, making them both immigrants and natives. Like the indigenous peoples of North America, systemic oppression in the form of violence, theft of land and cultural artifacts, anddisproportionate levels of poverty.

Asian Americans have a unique challenge when it comes to finding their place in the American story. Although America is a land of opportunity, racism has repeatedly tried to cheat immigrants out of their dreams, and the milestones Asians achieved has been used as proof that racism doesn’t exist and to drive a wedge between Asians, the model minority, and other oppressed groups like Latin and African Americans. Pacific Islanders continue to fight for recognition in their homelands and to reclaim their traditions and lands. The Asian American Pacific Islander story is one of contradiction and diversity, but the myriad of facets are tied together by triumph and endurance in the face of adversity and, contrary to popular stereotypes, a very American refusal to back down.

What Is Asia?

ASIA IS NOT A COUNTRY. Asia is the world’s largest continent, with forty-eight countries, six of which are non-United Nations, and six dependent territories. Geographically, Asia is divided into four sections: East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and West Asia.

ASIA IS NOT A COUNTRY. Asia is the world’s largest continent, with forty-eight countries, six of which are non-United Nations, and six dependent territories. Geographically, Asia is divided into four sections: East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and West Asia.

East Asians and their cultures are what people generally picture as the face of Asians: Chinese, Japanese, and Korean people. China, Japan, and South Korea are all major world powers who deal closely with the United States, while North Korea is an infamous dictatorship and the subject of U. N. sanctions and superstitions. Each country has its own culture and language, along with smaller tribal minorities who dwell within the population. China is home to fifty-six ethnic groups, ninety percent being Han Chinese. Japan and Korea are also largely monoethnic countries, but minorities like the Ainu people of Japan or fifty-five ethnic minorities in China, including Tibetans, Mongolians, and hill tribes.

South Asia is generally assumed to be India, but it also encompasses Pakistan, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and the Maldives. Sometimes Afghanistan is considered a South Asian country, as it is on Pakistan’s western border, but Afghanistan has always been a crossroads and could be considered West Asian. Although they come from only a few countries, South Asians belong to hundreds of different individual cultures each with their own traditions and languages. India alone is home 1.339 billion people as of 2017 and divided into twenty-nine states, each with their own way of life, four major world religions (Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, and Sikhism), twenty-two major languages, and a thirty thousand year old civilization.

Southeast Asia consists of Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, Myanmar (Burma), Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, East Timor, and the Philippines. During the later half of the twentieth century, several dictatorships, civil wars, and foreign powers’ interferences, like the Vietnam War, have made life difficult for the people. Southeast Asia is incredibly diverse in its ethnic makeup, which varies with each country. Currently, the largest groups are the Javanese, who come from Indonesia, and the Vietnamese. The Hmong, Malays, Filipinos, Khmer, and thousands of indigenous groups have inhabited these countries for thousands of years. There are also large Chinese populations due to imperialism and unrest in China.

West Asia, also known as Southwest Asia, or Central Asia, is a diverse area of mountains, deserts, river valleys, forests, and inland seas. Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Cyprus, Gaza Strip, Georgia, Iran, Iraq, Palestine, Jordan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Qatar, Oman, Turkey, West Bank, Syria, and Yemen are all Asian countries with diverse populations. The Middle East’s racial population consists of Arabs, Persians, Kurds, Jews, and other ethnicities. Lately, political turmoil have driven droves of refugees to seek asylum in Europe and America. Too many are refused entry, and those that are allowed face violence, xenophobia, and identity crisis in their new countries.

What About the Islands

Pacific Islanders come from a plethora of islands in the Pacific Ocean, namely Polynesia, New Zealand, Micronesia, Micronesia, and Hawaii. The Philippines are influenced by the Pacific Island

and have a blend between indigenous and Chinese/mainland Asian culture. Famous islands include New Zealand, Tahiti, the Samoan Islands, and Tonga, each with their own tribes and cultures. Pacific Islander tribes include the Samoans from the islands of the same name, the Maori of New Zealand, Tahitians from Tahiti, and so many more. The ancient Polynesians were known for transporting entire villages, with people, furniture, and animals, in convoys of large canoes with sails from island to island, as far back as 1500 B.C.E.. They were able to navigate reading the currents and locations of the stars. Considering the huge gaps between islands and the danger of seafaring, the Polynesians were revolutionary.

How Did They Get to America?

The Asian American Pacific Islander story goes back to the genesis of the American story. Polynesians were rumored to have trade with indigenous people in South and Central America. Asian contact with the Americas dates back to the 1500s, when Filipino sailors, whose country was then under Spanish rule, visited New Spain port cities to trade and later settle down. In 1778, British Captain James Cook landed in Hawaii, which he dubbed the Sandwich Islands. Although the Hawaiians killed him, word got around, and Hawaii became a popular stop for whalers, traders, and missionaries looking for converts. The contact with people from the East and West exposed the Native Hawaiians to diseases like tuberculosis, measles, and venereal disease, killing dozens of thousands of people. Europeans and American outnumbered the indigenous tribes and came to own most of the land, which they used to grow cash crops like sugar and coffee. The natives saw their religion, culture, and rights banned by this new government. The royal family of Hawaii tried to keep control of the islands for the natives, most notably Queen Liliʻuokalani, but in 1898, white settlers, backed by the U. S. Military, overthrew her and forced her to sign over the land.

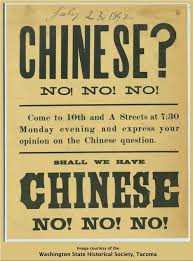

The first major wave of Chinese immigrants arrived after 1849, when the Gold Rush of California began. As many as 24,000 young Chinese men sailed to California to prospect for gold; the vast majority from southeastern China, where the port of Canton (Guangzhou) linked an isolated country to the rest of the world. These men took low wage jobs and less productive sites; they gained a reputation as hard workers who didn’t raise a fuss when their wages were significantly lower than their white counterparts. They established the first Chinatown in San Francisco and quickly grew, garnering resentment from whites who saw them as inferior and competition for jobs. They made money in the service industry, as cooks, cleaners, and launderers; in the 1860s, immigration spiked again for the dangerous job of building the Transcontinental Railroad that linked East and West coasts. The Chinese were believed to make up 90% of the workforce at one time, but they were left out of pictures and, until recently, history. Whites, including immigrants like the Irish, sought to drive them out with mob violence, lynchings, and unfair laws with no punishment, but rather encouragement, from the government.

Asian immigration to Hawaii began in the 1850s, when Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Korean, and Okinawan migrants were contracted for work on the plantations. They cultivated rice, coffee, and sugarcane. They worked twelve hour days for less than six cents an hour; housing conditions were deplorable. Anyone who tried to run away was beaten and imprisoned. Workers rebelled by refusing to work, attacking plantation managers, feigning illness, and even starting fires. Many natives and Asians married; today Filipinos are the largest ethnic group in Hawaii.

By 1882, the Chinese population of California was flourishing; Chinatown was growing, and families were coming over. Anti-Chinese sentiment was nothing new, but racism reached new levels on May 6, 1882 when the federal government passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. This was the first law prohibiting immigration based on ethnicity and has since become the “immigrant DNA” for America’s treatment of new arrivals, especially if those from black and brown countries. Chinese immigration was totally banned, save for traveling merchants, restaurateurs, and family members of those already living in America. New arrivals had to stay in barracks in immigration stations, the most famous of which is on Angel Island, established in 1910. Families were split up into men, women, and children; arrivals would be kept for two weeks to several years. They were interrogated, stripped, and subjected to humiliating medical examinations. Many became depressed; those who could write carved poems on the walls, expressing their confusion, misery, and hope in this new country. The treatment of the Chinese Americans essentially became the American template for handling immigrants, from unjust laws barring them entry to vilification in popular culture to detaining and splitting up families to demoralize them. If this sounds anything like the situation at the border between Mexico and America, where poor undocumented families are captured, separated, and imprisoned in terrible conditions, then it’s all the more apparent how history repeats itself in the worst ways.

By 1882, the Chinese population of California was flourishing; Chinatown was growing, and families were coming over. Anti-Chinese sentiment was nothing new, but racism reached new levels on May 6, 1882 when the federal government passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. This was the first law prohibiting immigration based on ethnicity and has since become the “immigrant DNA” for America’s treatment of new arrivals, especially if those from black and brown countries. Chinese immigration was totally banned, save for traveling merchants, restaurateurs, and family members of those already living in America. New arrivals had to stay in barracks in immigration stations, the most famous of which is on Angel Island, established in 1910. Families were split up into men, women, and children; arrivals would be kept for two weeks to several years. They were interrogated, stripped, and subjected to humiliating medical examinations. Many became depressed; those who could write carved poems on the walls, expressing their confusion, misery, and hope in this new country. The treatment of the Chinese Americans essentially became the American template for handling immigrants, from unjust laws barring them entry to vilification in popular culture to detaining and splitting up families to demoralize them. If this sounds anything like the situation at the border between Mexico and America, where poor undocumented families are captured, separated, and imprisoned in terrible conditions, then it’s all the more apparent how history repeats itself in the worst ways.

The turn of the twentieth century saw a boom in Asian immigration. Hindu and Sikh, Filipino and Japanese, and illegal Chinese immigrants arrived in droves, worrying the Americans about the “yellow peril.” Poor Indian farmers were contracted for labor in British Columbia, but exclusionary laws drove them down to Washington, Oregon and California, where they built communities close to the Mexican Americans. The Spanish American War resulted in the U. S. taking control of and waging war in the Philippines; Filipinos came to America for a multitude of reasons, from education to working on sugar plantations in Hawaii. In 1907, the Gentlemen’s’ Agreement between America and Japan sought to limit Japanese immigration, but from 1908 to 1924, picture brides from Japan crossed the ocean to marry men they only knew from photographs that glossed over the hardships they would face. Asians who emigrated to Latin America and Canada as trafficked servants and displaced workers, where they still make up significant parts of the population, crossed the borders and bypassed exclusionary laws. After the Great Earthquake of 1906 destroyed records in San Francisco, Chinese “paper sons” were able to get using false documents saying they were children of native born Chinese.

Immigration trickled to standstill after immigration quotas were passed in

1924, allowing only a single digit percentage of every nationality to enter America. However, this was revised in 1956 and 1965 as Asian immigration boomed again in the aftermath of World War II. The devastating conflict lasted several years and included the Japanese internment in America, Japan’s takeover of China and Southeast Asia, and countless atrocities of war; refugees from China and Southeast Asia fled war torn homelands that were turning into communist regimes. In 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed. Asian populations doubled, and as the U. S. sought diplomatic relations with pre-communist China and later Japan, treatment of Asian immigrants had to improve to reduce tensions.

New kinds of immigrants came to American shores from the 1940s to the 1960s. American soldiers fighting in Japan, Okinawa, China, and Korea brought home war brides, while survivors of the war flocked to the West Coast for jobs. White Americans in Korea brought home the first major wave of Asian adoptees, who found themselves caught between their Asian heritage and their white families’ cultures. Students from new communist regimes like China fled political oppression to study at American universities. Highly skilled workers like doctors, nurses, and soldiers left political unrest in the Philippines and became the second largest Asian ethnicity in America, behind the Chinese Americans. The Nationality Act of 1965 abolished the 1924 quotas, allowing for an overflow of South Asians to journey to the United States, whether from India and Pakistan, Britain and Africa, or the Caribbean.

Southeast Asian immigration reached an all-time high during the 1970s; the U. S. waged war on behalf of South Vietnam to stop communism from North Vietnam for ten years. Although it was supposed to be for the South Vietnamese people, the American intervention resulted in villages of women and children being massacred, the North Vietnamese gaining more and more land, and the rape and exploitation of countless Vietnamese women. In 1975, America pulled out of South Vietnam, allowing the North to take over. Vietnamese in the South, who feared being sent to communist re-education camps (read: concentration camps) scrambled to find flights to the U. S.; a lucky ninety-five thousand left their homeland by air. Poorer relations became “boat people” who braved deadly ocean voyages to Thailand, China, and Cambodia, but disputes with those countries drove many to the United States. Meanwhile, American bombings in Cambodia and Laos plus the rise the of Khmer Rouge, communism, and genocide drove Hmong, Cambodian, and countless other groups to America.

A similar phenomenon currently brews with Arab and West Asian Americans seeking asylum. Thanks to meddling from European colonizers and the American government, from businessmen worried about access to oil to the CIA organizing coups in Iran, plus the formation of Israel, the Middle East has turned into a war zone, with Central and West Asia caught in between. The rise of militant terrorists taking over countries in the name of a twisted form of Islam and violent dictatorships that oppress the ordinary people have driven myriads to flee by boat or plane. The Syrian refugee crisis, the War on Terror, the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in Iraq, and the unrest in Afghanistan have dominated the news and politics for the last two decades, but American politicians and media have unfairly vilified Arabs and Middle Eastern peoples as violent terrorists when they are quite the opposite: peaceful, normal citizens who have lost their old lives running from the terrorists. The ones fortunate enough to enter the United States have to adjust to a new country that views their religion and culture with suspicion and hatred, often resulting in bullying, exclusion from jobs, or hate crimes from American terrorists that try to make people feel unwelcome.

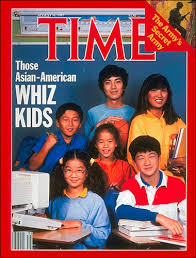

Although the postwar economy and repealing of some racist acts improved the situation for Asian Americans, systematic racism persisted. During the Cold War, the government and secret services spied on and falsely accused Chinese communities of communist conspiracies. Chinese professors and scientists could find themselves unfairly jailed for prejudiced accusations. Although exclusionary acts based on nationality were banned, the government still didn’t want to let in too many immigrants. They narrowed down the amount of people they had to accept by favoring skilled workers: students, doctors, technicians looking for educational or career opportunities. Examples include students from China and Taiwan or Indian Americans in the hospitality industry. Media cited Asian Americans as models of success and meritocracy, especially to shut up civil rights activists; however, the model minority myth ignored the poverty of these communities, the higher rates of mental illness and abuse, the exploitation of Asian women, and the fact that America constantly tried to kick these people out while acting as a safe harbor.

Pacific Islanders, which include Native Hawaiians, Polynesians, and Micronesians, have become both native and immigrant. Polynesians and Micronesians also saw Europe and the U. S. take over their islands; the turmoil caused by imperialism compelled thousands to leave home for a life in Hawaii or California. Samoa and Guam are currently U. S. territories, but the inhabitants are not considered U. S. citizens and do not enjoy the privileges. Companies and the government are still trying to wrest the Pacific Islanders’ remaining lands, much of which is sacred, but grassroots organizations of indigenous folk continue to lobby for land returns, the preservation of cultural property, and accountability for the genocide, rape, and stigmatization of their people. In 1998, one hundred years after the U. S. stole Hawaii, President Bill Clinton formally apologized to the Hawaiian people for his country’s actions, but independence for Hawaii still has not come.

Asian Americans Today

Asian Americans are currently upheld as the model of American success. Overachieving students, affluent family, tiger mothers, computer science nerds, submissive and docile citizens. This view is contrasted against stereotypes of African Americans, who suffer police violence and higher rates of poverty and stigmatization due to four hundred years of specialized racism. However, the model minority myth fails Asians in so many ways.

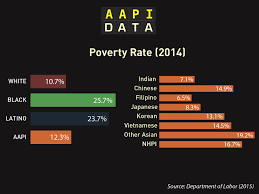

For starters, although Asians overall have a higher median income than any other racial group in America, poverty is a huge problem. Although Chinese Americans have higher median annual incomes, their poverty rates are 14%, higher than the general U. S. population. Refugee communities, like the Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Bangladeshis, suffer disproportionate rates of poverty (15-20%), incarceration, and lack of education. Poor immigrants,  many of whom are undocumented, work in the service industry and face low wages and exploitation by bosses. Asian Americans in California grew the most in unemployment, while they are the poorest racial group in New York City. Cambodian Americans face risk of deportation to a country they no longer know. Even Chinese American scientists have been brutally assaulted and arrested for supposedly conspiring with their communist homeland, like physicist Xiaoxing Xi in 2015. Chinatowns are increasingly at risk for gentrification; ethnic enclaves tend to have the highest rates of poverty. Harvard University recently got sued for requiring Asian students to earn higher scores than white students for admission. The model minority myth is not a positive stereotype, as if such a thing could exist; it prevents poor Asians from getting the help they need and pigeon holes and dehumanizes Asians who fit the stereotype, cheapening their hard work and creating unfair expectations. Sadly, hordes of Asian Americans do buy into the Model Minority Myth in hopes of achieving the American Dream and assimilating, but no matter how hard they try, they will always be “other.”

many of whom are undocumented, work in the service industry and face low wages and exploitation by bosses. Asian Americans in California grew the most in unemployment, while they are the poorest racial group in New York City. Cambodian Americans face risk of deportation to a country they no longer know. Even Chinese American scientists have been brutally assaulted and arrested for supposedly conspiring with their communist homeland, like physicist Xiaoxing Xi in 2015. Chinatowns are increasingly at risk for gentrification; ethnic enclaves tend to have the highest rates of poverty. Harvard University recently got sued for requiring Asian students to earn higher scores than white students for admission. The model minority myth is not a positive stereotype, as if such a thing could exist; it prevents poor Asians from getting the help they need and pigeon holes and dehumanizes Asians who fit the stereotype, cheapening their hard work and creating unfair expectations. Sadly, hordes of Asian Americans do buy into the Model Minority Myth in hopes of achieving the American Dream and assimilating, but no matter how hard they try, they will always be “other.”

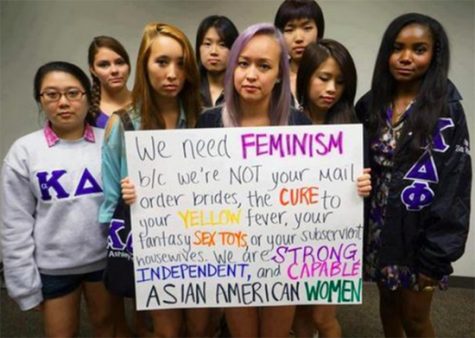

The othering of Asians encompasses a variety of stereotypes and marginalization. Asian men are stereotyped as effeminate, backwards, unappealing partners, which gets them passed up for leadership positions at work and on dating sites. The women are portrayed as exotic, submissive China dolls or sneaky dragon ladies, leading to non-Asian men to prey on them. Too many Asian women have been rudely questioned about their “strange, mysterious” background by cads looking for a good time; currently, over thirty thousand Asian women are trafficked into America every year. The model minority myth also glosses over the continued xenophobia and hate crimes Asians of all ethnicities face. In 1982, when Chinese Americans were being praised as math science geniuses, Vincent Chin was beaten to death by two auto workers angry that Japanese cars were overcoming the American auto industry. The murderers confessed to the crime, but they only paid a fine and did not spend a day in jail. The Chinese community was outraged and mobilized into a major protesting force, demanding justice for Chin, but the murderers still walked free. Even today, the yellow peril lives on; the success of affluent East Asian students has been seen as a threat to mainstream white society, as seen with Harvard’s requirements, President Donald Trump’s attempts to put limits on student visas for Chinese students, and a spike in hate crimes against Asians after Trump declared China a foreign enemy.

Another example of the othering of Asian Americans comes in microaggressions. Asian children are 20% more likely to get bullied, whether it’s about being an overachiever, their parents having an accent, or bringing ethnic food to school lunch. Nearly every Asian American can recall at least few instances of racial bullying and carrying a sense of shame around their parents’ culture. The majority of books and movies about immigrant children’s experiences, especially those by Asians, includes a protagonist grappling with a cultural identity that has been mocked or misunderstood by peers. Then there are those who take too much interest in cultures different from their own to the point where it crosses the line. Hippies appropriating sacred symbols like the lotus or Buddhas, anime freaks who (often inaccurately) wear kimonos as costumes and see Japanese as fandom lingo instead of a language, and K-pop fans who fetishize East Asian men without acknowledging the tribulations Korean Americans face may think they’re being helpful, but “yellow fever” is not any better than “yellow peril.” Learning about cultures and liking anime is fine in itself, but when non-Asians start spreading misconceptions about the culture, appropriating sacred or significant symbols, and barging into intra-community discussions they can’t understand in the name of fandom, then there’s a problem. The cultural appropriation debate has been heated over the past several years, but the best way to navigate the boundaries of cultural appreciation versus appropriation is simply to ask permission from the marginalized group in question.

Another example of the othering of Asian Americans comes in microaggressions. Asian children are 20% more likely to get bullied, whether it’s about being an overachiever, their parents having an accent, or bringing ethnic food to school lunch. Nearly every Asian American can recall at least few instances of racial bullying and carrying a sense of shame around their parents’ culture. The majority of books and movies about immigrant children’s experiences, especially those by Asians, includes a protagonist grappling with a cultural identity that has been mocked or misunderstood by peers. Then there are those who take too much interest in cultures different from their own to the point where it crosses the line. Hippies appropriating sacred symbols like the lotus or Buddhas, anime freaks who (often inaccurately) wear kimonos as costumes and see Japanese as fandom lingo instead of a language, and K-pop fans who fetishize East Asian men without acknowledging the tribulations Korean Americans face may think they’re being helpful, but “yellow fever” is not any better than “yellow peril.” Learning about cultures and liking anime is fine in itself, but when non-Asians start spreading misconceptions about the culture, appropriating sacred or significant symbols, and barging into intra-community discussions they can’t understand in the name of fandom, then there’s a problem. The cultural appropriation debate has been heated over the past several years, but the best way to navigate the boundaries of cultural appreciation versus appropriation is simply to ask permission from the marginalized group in question.

A very serious, alarming form of oppression against South and West Asians is Islamophobia, a prejudice against Muslims. Thanks to events like 9/11, warfare in the Middle East, and the rise of fundamentalist Muslim cults like ISIS, Islam, a religion that emphasizes faithfulness to God, charity, and family, has been branded an oppressive religion. Muslims, or anyone who looks like they could belong to the religion, are profiled as terrorists, battered wives in need of a usually white savior, and dangers to society. The turban has been labeled a sign of terrorism, when it is a sign of a man’s faith in God and human goodness, while the hijab represents female oppression for white feminists, when it is a Muslim woman’s show of her faith, culture, and protection from leering men. South Asians and Arab people, whether they are Hindu, Muslim, Christian, or atheist, have been spied on by the government, shot down in their houses of worship, had acid thrown on their faces, their homes and property vandalized, and denied asylum after fleeing war torn countries based on unfair stereotypes.

Despite being called the model minority, Asian Americans still suffer from the effects of racism and continue to fight it. College organizations, protest leagues call out individual examples of racism from celebrities, businesses, and governments of all scales, and thousands of normal people have shared their experiences on social media. Asian American celebrities have clapped back against whitewashing and racist portrayals in the media while calling for and creating diverse media of their own, like To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before and Crazy Rich Asians. Asian Americans have been fighting for their rights ever since they first landed on these shores; Chinese Gold Rushers dragged their attackers to court and demanded equal educational opportunities for their children, while Filipinos fought off the U. S. Army for three years when their islands were invaded. Countless grassroots movements have condemned the desexualization of Asian men and the hypersexualization of Asian women, providing legal and emotional support for survivors of domestic abuse and educating their communities. Muslim communities and organizations strive to educate the public about their religion and protect themselves from American terrorism in the forms of racist politicians, hate crimes, and unfavorable representation. Although too many Asians still feel ashamed and try to assimilate into the American system, in an era of social media and activism, the people are demanding more representation, rights, and respect that’s been overdue for centuries.

Pacific Islanders Today

Pacific Islanders suffered devastating consequences from colonization. Thanks to Americans and Europeans stealing their land and passing laws that denied them voting rights, they now have lower rates of educational attainment, lower median annual incomes, and an overall poverty rate of 17.3%. Obesity, diabetes, smoking, and alcoholism levels are higher, but private healthcare insurance coverance is lower than other racial groups. 32.7% rely on public health insurance while 6% are not covered at all. Pacific Islanders have significantly less access to adequate health care thanks to limited insurance, poverty, and isolation from health centers.

Although Native Hawaiians do not live on federally recognized reservations like North American natives, there are seventy-five tribal areas set aside for them that function similarly. Housing is a disaster; although they only make up 10% of the population, Native Hawaiians are 30% of Hawaii’s homeless. The land was set aside to improve the lives of natives, but the government requires that one must prove themselves “Hawaiian” enough with a blood quantum test, which is impossible for mixed race people who still suffer from anti-native racism and need those homes. As of 2015, 21,000 people were on waiting lists for a Hawaiian homestead that rightfully belongs to them.

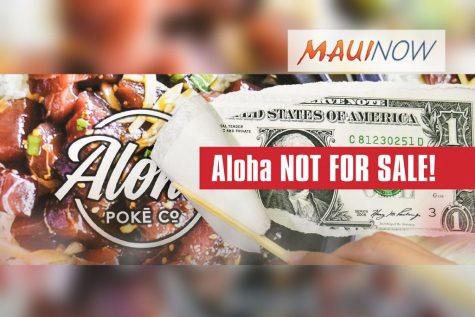

Add on the bastardization and packaging of Hawaii’s culture. Christian missionaries and American businesses turned Hawaii into a tourist hotspot, using the “exotic, welcoming” Aloha spirit to allure travelers. Hawaii’s sacred customs and artifacts like hula, leis, luaus, and surfing, all of which were forbidden to the native population when they were first conquered, became recreation for tourists. In 2016, a video of a Hawaiian man being beaten by a Honolulu policeman for chanting over a seal for an ancient tradition surfaced; the onlooking crowd seemed to express more outrage over the seal than the innocent man being assaulted. The stereotype of a carefree, happy people erases the reality of poverty and injustice for the real Hawaiians, who still are losing their sacred land to colonizers, like Mauna Kea. The hula girl caricature has resulted in higher rates of sexual violence against Native Hawaiian women from non-native men; stigmas about the higher rates of obesity and substance abuse have been used as an excuse to incarcerate the men.

Add on the bastardization and packaging of Hawaii’s culture. Christian missionaries and American businesses turned Hawaii into a tourist hotspot, using the “exotic, welcoming” Aloha spirit to allure travelers. Hawaii’s sacred customs and artifacts like hula, leis, luaus, and surfing, all of which were forbidden to the native population when they were first conquered, became recreation for tourists. In 2016, a video of a Hawaiian man being beaten by a Honolulu policeman for chanting over a seal for an ancient tradition surfaced; the onlooking crowd seemed to express more outrage over the seal than the innocent man being assaulted. The stereotype of a carefree, happy people erases the reality of poverty and injustice for the real Hawaiians, who still are losing their sacred land to colonizers, like Mauna Kea. The hula girl caricature has resulted in higher rates of sexual violence against Native Hawaiian women from non-native men; stigmas about the higher rates of obesity and substance abuse have been used as an excuse to incarcerate the men.

The Pacific Islander story is both saddening and infuriating. However, the people have not given up. Elders pass down their languages and traditions to the new generation, and organizations fundraise, protest, and appeal for reparations, the protection of sacred land, and recognition of tribal rights. Actors like Jason Momoa and Dwayne Johnson act as voices for their communities, speaking for Pacific Islander causes. Authentic ceremonies, luaus, and celebrations are still held. More and more young people are attending universities and educating the general population on the truth. A few college groups have condemned Hawaiian party themes and offered insight into the toll it takes on the real people. Although there is so much more left to be desired, the Pacific Islander community is gaining visibility and still has hope for justice.

May Is Asian American Pacific Islander Month

In 1978, President Jimmy Carter signed the joint resolution that declared May the month to commemorate Asian American and Pacific Islander heritage, history, and culture. May was chosen since it marked the anniversary of the first Japanese immigrants on May 7, 1843 and the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad on May 10, 1879. Asian Americans have struggled as immigrants, whether blatantly or invisibly, since the 1800s, but their voices remain strong with a history of endurance, pride, and activism. Pacific Islanders were robbed of their land, but they refuse to back down and nourish their communities with the strength of their culture’s survival and the ongoing fight to reclaim their land and liberties. Racism against and within the Asian American Pacific Islander community started long before today and will not end anytime soon, but as their voices in books, documentaries, movies, and movements step into the spotlight, they become powerful Americans who can never be robbed of their dignity and freedom. May is Asian American Pacific Islander Month, and, from me, a Chinese American adoptee, I will say this: It’s our time.