Why Diversity in Media Matters

January 24, 2019

I was adopted from China in 2003, by a white mother and father, at the age of one, too young to remember anything, including the language. As a child, my only connections to China consisted of watching Disney’s Mulan, taking Chinese classes for a year as an unfocused six year old, and listening to my parents’ story of my adoption. As I got older, however, this fun fact about my life became a source of shame, something I wanted to wipe away as soon as possible. Being Chinese meant being asked if I spoke the language (I don’t), if I ate dog (a rare event from one city that most Chinese condemn and are campaigning to end), if I watched anime (rarely), or, best of all, how it felt to come from a backwards culture that was only good for kung fu and fortune cookies and was lucky to be rescued like some stray dog by two nice Americans. These incidents fortunately weren’t common, but they stung. Being Chinese became something to be ashamed of, something I hoped to shed by being American (read: not Asian) enough. I didn’t feel Chinese on the inside; I had white parents, I didn’t speak the language, and I avoided other Asian people, especially if they fit the stereotypes. I wished I didn’t come from a culture associated with weirdness, animal abuse, and rice. Being one of a few Chinese kids in my school didn’t help. Simply put, I hated being Chinese.

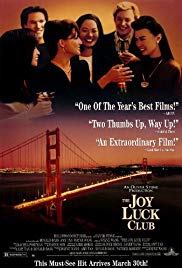

But in my freshman year, my English teacher had us watch the Joy Luck Club, a film adaptation of Amy Tan’s classic novel. The Joy Luck Club explores the lives of four Chinese women who play mahjong together and their Americanized daughters; both mothers and daughters face adversity and heartbreak while struggling to understand one another. I had read the book before and sympathized more with the daughters, unable to empathize with their traditional mothers and how they kept their culture alive despite having been abused within it. Even today, whenever I look up video clips on Youtube, commenters attribute the women’s suffering to “Oriental culture”, something they are not part of but believe should be modified to fit Western standards.

I have some lousy memories while watching the movie. Some classmates had a ball imitating and mocking the women’s accents; I was called a lizard and a dragon in a fake Chinese accent. But as I watched these Chinese women, who looked like me, take the center stage, navigating the difficult dance between Chinese culture and American sensibilities in a genuine, non-stereotypical way, a funny sensation washed over me. All those feelings of shame and embarrassment became sharp weapons of anger. The belief that being Chinese made me uncool, that I could shed the color of my skin to fit the norm, that being white would make me better, lost its grasp.

For the first time in my life, I felt proud to be Chinese. I felt proud to be Asian. It was part of me, something that I could not and should not deny. I belonged to this beautiful, complex story, and no one could take that away. I laughed at the women’s witty observations on Chinese American life, relating to them despite having a completely different coming to America story. I cried at their tragedies and triumphs, especially when I saw a mother forced to abandon two babies, something my birth mother had to do. I finally felt seen, acknowledged, not as a stereotype or a backwards immigrant needing to assimilate, but a person worthy of basic respect.

***

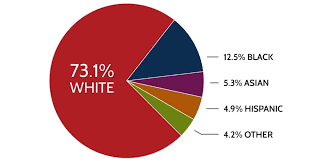

People frequently laugh at promoting diversity in media, complaining that it’s not necessary and sidelines the white majority. Some point to side characters in popular movies, such as Dionne from Clueless, or the occasional protagonist of color, such as Disney’s prince Aladdin and a string of Eddie Murphy characters. Others demand to know why Black Entertainment Television (BET) and Asian dramas aren’t enough. Then there are those who don’t see anything wrong with a mostly white Hollywood and see diversity as a gimmick to make ticket sales.

But it matters.

Diversity matters when people of color (POC) are being picked on, denied jobs, or assaulted for their background. It matters when minority children are picked on for their ethnicity. It matters when oppressed groups begin to hate themselves. Numerous studies have shown that children of color have lower self esteem than their white counterparts when watching television or reading books thanks to stereotypes or lack of material. It matters when members of marginalized communities are sidelined or have their achievements forgotten. It matters that their voices and issues get a platform so that their stories will be remembered for posterity.

I could go on all day, but here are the four main reasons why diversity in the media matters.

Disclaimer: This article focuses on racial diversity, but the representation of LGBT and disabled folks matters as well, and for POC with disabilities, mental illness, and different sexual orientations, this article is for them too.

It spreads awareness.

Literature has been used as a political weapon that holds immense sway over public opinion. When marginalized people call for representation, they are asking for a chance to have their experiences- their oppression, their culture, their triumphs- shared with the world and get the conversations started. Representation exposes wrongs hidden or ignored by society and forces everyone to think and talk about it. For example, back in the 1800s, former slaves and abolitionists exposed the injustice of slavery by writing about the slaves’ hardships. Famed abolitionist and writer Frederick Douglass published a memoir detailing his life as a slave; he would continue to write articles, letters, and books about the African American experience, giving black people a voice in a country that denied them their humanity. Over a hundred year and fifty years later, Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give serves as a wake-up call to the police brutality and stereotypes black people face despite America’s post racial status. “Art has always been political,” tweeted comedian and Academy Award nominee Kumail Nanjiani, whose work frequently focuses on the injustices Pakistani immigrants like his parents face. “Music has always been political. Books have always been political. Movies have always been political.”

It allows marginalized groups to explore their cultural legacies.

Diverse literature allows marginalized groups to explore the history and meaning of their identities. Folks who campaign for inclusivity often refer to good representation as “made by poc for poc.” In other words, the target audience is not mainstream society, but the people being represented. The point is to make a community feel seen and related while dissecting their identities and issues.

“I’m Jordanian American,” said senior Reta Haddad. “I have two cultures, I see things from two different perspectives. That means I’m different, and I’m proud of it, especially since there’s so much hate and ignorance going around. When I see a character who looks like me, it makes me feel like I have a connection with them. It tells me and my family that we’re not the only one [Jordanian Americans], that we’re not alone in the world.”

Books exploring immigrant identities and culture provide a safe space. Like what the Joy Luck Club did for me, multifaceted literature lets POC feel seen, understood, and connected. It helps people make sense of their culture, their perception of it, and feel pride in who they are.

It dismantles stereotypes.

Popular media is not totally white. There might be a few African American characters, maybe an Asian or Latinx sidekick or extra. Natives almost never get roles, unless it’s a Western. The majority of marginalized characters have two things in common: they’re supporting characters, and they’re more than likely stereotypes. Remember the sassy black best friend from the romantic comedies? Or the East Asian mystical martial artists who are props to further a white hero’s journey? Hollywood tries to fulfill demands for diversity with minimal effort or thought by casting POC actors in big movies, but only as side characters with little development.

Why does this matter? Stereotypes become relevant when they become the face of a race or group. When black men are profiled as gang members or drug dealers due to a movie’s racist portrayal,

they get undeserved suspicion that can get them ostracized, denied jobs, and manhandled by the police. Latinos face similar racism, pigeonholed as illegal immigrants, troublemakers, and fiery lovers; these tropes lead to xenophobes telling them to go back to Mexico, unwarranted drug searches, or even a call to ICE for no good reason. One in three Native American women will face domestic violence or rape; many natives argue that this violence correlates with the media’s image of a docile, exotic Native princesses (think Pocahontas). Asian men are painted as less attractive and manly than other races, while the women are expected to be exotic, submissive dolls; although numbers vary by different ethnic groups, Asian women face higher rates of sexual harassment and assault from men wanting a docile lover while the Asian men get passed up on dating websites and for executive positions. Stereotypes translate into reality, unfortunately.

Media made by and for minorities ends the terrible cycle of stereotypes. It humanizes them, giving them their autonomy, an accurate look at their culture, and a chance to see themselves understood. For privileged audiences, diverse media is an educational opportunity to understand another person’s experience through their eyes, not through a watered down, mainstream lens. The black or brown person gets to be the hero; speaking of which…

Everyone should get to see themselves as the hero.

And sometimes, POC don’t want a political or cultural story. Sometimes it’s nice to just be the hero- a normal human being who looks like them. One might ask why a diverse cast is necessary if race isn’t the focal point, or when minorities are, well minorities. But the question should be: why not? There’s no reason why POC shouldn’t see themselves in normal settings, where their background is respected but not the central focus. America is a diverse place; even small percentages can make up millions of folks who desire to see their likeness in media. Besides, people are people first, and POC should get to see themselves represented as such.

One of my favorite examples is To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before, a romantic comedy on Netflix based on the bestselling young adult series, which a biracial Korean Caucasian protagonist, Lara Jean Covey. Lara Jean’s character arc focuses on her romances and teenage drama, but the Korean American author, Jenny Han, wanted a heroine to reflect herself and the millions of Korean American girls like her. Lara Jean’s heritage is important to her and referenced occasionally, but most of her story is no different from that of any other teenage girl, which is what Han was aiming for. When producers wanted to turn the popular book into a movie, almost all of the studios wanted to whitewash Lara Jean and her family, but Han was adamant that Lara Jean remain Korean; Asian actress Lana Condor got the part, and the movie has since become a hallmark of representation and YA romance.

***

With all these different reasons, it can be difficult to understand what exactly is being asked. The demand for good depiction from so many different people is overwhelming at times, and sometimes it seems like nothing will ever be good enough. Someone will always be irritable, but most simply want to see themselves shown with accuracy and empath, not as a stereotype or minor role, but a fully realized protagonist who can relate to their experiences. The best representation comes from diverse creators, who have the best understanding of their own cultures and narratives. If producers and publishers want to help, the optimal solution would be to give marginalized artists the resources to share their ideas. Normal consumers can support heterogeneous filmmakers, writers, and artists by reading their books, going to their movies, or spreading the word.

“The world is diverse; diversity helps everyone see the world through a different culture and experience from their own,” said English teacher and founder of the Lit Club Carl Dunlap. “As a teacher, I try to pick people from different perspectives than the typical protagonists of literature, like women and African Americans. The more perspectives I expose students to, they become more interested in other aspects of life. We should keep branching out; it doesn’t hurt anyone, and we could use a lot more empathy. Make diversity the norm, because that’s the way the world is.”

None of this is to say that white people don’t matter. Many of my favorite books and movies feature white protagonists. I don’t think there needs to be a decrease in white actors. What this article is trying to articulate is that people of color need a chance to step into the spotlight as well. With campaigns like #RepresentationMatters and “WeNeedDiverseBooks gaining steam, minority celebrities using their power to push for change, movies like Black Panther and a wonderful plethora of diverse books coming out, and Hollywood finally waking up to how much money they make by granting POC humanity and heroics on the screen, it’s a wonderful time for change.